Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, The University of Queensland and Justine Bell-James, The University of Queensland

The Australian government has stepped up its campaign this month to prevent the Great Barrier Reef being listed as a World Heritage site “in danger” at international meetings next year.

The World Heritage Committee — the international body that oversees World Heritage sites — has shown increasing concern about the future of the reef over the past three years, and in response has threatened to list the reef as a World Heritage site “in danger”.

Australia has argued that it is meeting the conditions set by the World Heritage Committee to protect the reef (even though some feel this is at face value only). While valid concerns remain over the detail within the government plans for the reef, we argue that it would be prudent for UNESCO to defer making the call. If the Committee listed the reef as “in danger”, it would be giving up its significant lever to prompt Australia to step up, and thereby jeopardising the future World Heritage Area status of one of our most precious national treasures.

Road to danger

How did we get here?

First, there was the build-up of worrying reports which revealed that the Reef has been losing its reef-building corals at a rapid rate since the early 1980s. These alarming reports have continued with the latest report showing a loss of 50% since the early 1980s. Much of this change can be traced to human impacts from deteriorating water quality and the declining resilience of coral reefs in response to impacts such as crown-of-thorns starfish outbreak, climate change and disturbances from cyclones and storms.

Then there was a sudden appearance of major gas liquefaction facilities on Curtis Island inside the World Heritage area, apparently in contravention of the World Heritage Convention yet authorised by the previous Queensland government.

This was enough to spark an “invitation” by the Australian government to the World Heritage committee of UNESCO to visit the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage property.

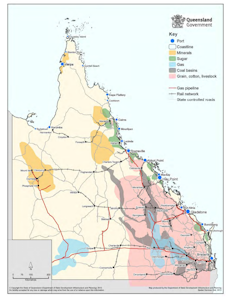

The visit ignited a political storm. The more committee members learned, the more they became concerned about the direction that the Australian and Queensland governments were taking with respect to the reef. This led to a damning report from UNESCO which criticised management of the Great Barrier Reef and the apparent planned proliferation of port facilities up and down the Queensland coast. The report specifically recommended no new port development outside the established port areas of Abbot Point, Gladstone, Hay Point and Mackay, and Townsville.

Most importantly, the UNESCO report also stated the real possibility that the GBR property might be listed as a World Heritage site “in danger”. To many, this outcome would be a major blow to Australia’s reputation as an environmentally responsible nation, with clear ramifications for its iconic tourist industry, worth around A$6 billion dollars each year.

These developments quickly re-focused the attention of the Australian public, as well as state and federal governments.

Lines in the sand

Perhaps not unexpectedly from such a politically explosive issue, a range of actors entered the fray. A line was drawn with mining largely on one side and reef experts on the other.

The spotlight also fell on other potentially harmful activities. The dumping of three million cubic metres of dredging spoils from the expansion of Abbot Point, for example, was at first permitted, but subsequently reopened for assessment as the debate heated up. The federal government is now considering a land-based option for dumping dredge spoil.

Key experts left their positions within the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, concerned leaders held Senate inquiries, and commentators across a spectrum lent words to the growing controversy.

Interestingly, the federal government (following the reconsideration of the Abbott Point issue) had in the meantime begun to tackle the dredge spoil issue across a wide range of other projects, reducing about 47 million cubic metres of planned disposal in the marine park to zero. These difficult decisions were naturally welcomed by the UNESCO committee, amid an otherwise confusing mass of opinion and rhetoric.

Should the reef be listed as ‘in danger’?

This question has been examined continuously over the three-year saga. On one hand, state and federal governments have arguably come a long way to meeting the concerns of the UNESCO World Heritage committee. On the other, the health of the reef is still declining and consequently more needs to be done.

The Queensland Government has recently introduced the Ports Bill that supposedly restricts further port development along the Queensland coast to ports at Brisbane, and four “Priority Port Development Areas”, currently defined to include the four ports identified by UNESCO. The Bill also restricts dredging for new and existing port facilities for the next 10 years, except in priority ports. This Bill consequently is a step towards implementing the UNESCO recommendations, and demonstrates that the threat of an in-danger listing has provided a lever for reform.

At the same time, the state and federal governments and their partner agencies developed a long-term sustainability plan for the reef, while expanding activities with respect to tackling the water quality issue with its partners.

The World Heritage Committee urged Australia in 2011 to undertake a strategic assessment of the World Heritage Area and develop a long-term plan for protecting the Outstanding Universal Value of the reef (the basis for its World Heritage listing). While there has been legitimate criticisms from the expert community (including one of the authors of this article, O.H-G.) of the plan given it is vague on quantitative targets and specific strategies, and strangely silent on the implications of a growing climate crisis for the Great Barrier Reef, many of the efforts of state and federal governments have gone a long way to meeting the recommendations of the World Heritage Committee.

With this in mind, there is an argument to say that the World Heritage Committee should not re-list the reef as “in danger”. After all Australia appears to have met most of the recommendations and should, on the face of it, be recognised as such - perhaps with the caveat that it has much more to do.

Especially given that current and proposed actions are unlikely to stem the catastrophic loss of key organisms such as reef-building corals.

And lastly, it would seem ill-advised that the World Heritage committee remove one of the only levers it currently has over the treatment of the World Heritage listed GBR. The threat of an “in danger” listing is a major incentive for Australia to improve its game, and has already prompted some reform. With this lever gone, the influence of UNESCO would largely disappear along with, most probably, any political will to prevent the further decline of the once-pristine reef.

The devil is in the detail

There are, however, a number of important issues that need to be resolved for the world to be reassured that Australia is taking its World Heritage responsibilities seriously. These issues, however, should be easily solved by both state and federal governments, especially given their efforts so far.

The Ports Bill, as drafted, leaves open a number of loopholes. UNESCO has expressly recommended no new port development in the World Heritage Area, but the Bill only prohibits any significant port development. What would be classified as ‘significant’ is not defined in the Bill but clearly needs to be.

Additionally, UNESCO recommended that port development be restricted to the four major ports listed above. These are termed priority ports in the Bill, and there do not seem to be any barriers to further areas being declared as such. Therefore the restrictions on new development (and dredging) could potentially be overcome by declaring a proposed port to be either (a) not a significant port development, or (b) a priority port. This needs to be resolved so as to reassure UNESCO and the Australian people that port development cannot proliferate across coastal Queensland through a loophole.

Consequently, there are several inconsistencies that must be ironed out if the actions of the two governments are to be robust and credible. The State and Federal government should take the opportunity to strengthen proposed legal protections to fully reflect UNESCO’s recommendations.

However, given the efforts of the Queensland and Australian governments to resolve these issues, it would be advisable for UNESCO to continue its patient prodding of the Queensland and Australian governments to improve the response to their concerns. The threat of an “in danger” listing has already sparked some reform, and may be enough to trigger further reform, without jeopardising the World Heritage Area status of the GBR.

These issues are not insurmountable but are required if we are to preserve one of Nature’s most spectacular ecosystems for President Obama’s daughters and the generations to follow.

This article was amended on December 18, 2014, to clarify the timeline of reports on the reef’s health, and the government agencies that developed the long-term sustainability plan.![]()

Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, Director, Global Change Institute, The University of Queensland and Justine Bell-James, Lecturer in Law, The University of Queensland

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.