It’s World Intellectual Property Day – a day to raise awareness of the role intellectual property plays in our daily lives, and to celebrate the contribution made by innovators and artists to the development of societies around the globe.

Some of TC Beirne School of Law’s ARC Laureate intellectual property researchers working in the area of food security talk about protecting IP and the role of IP in innovation and creativity.

Why is it important to protect intellectual property?

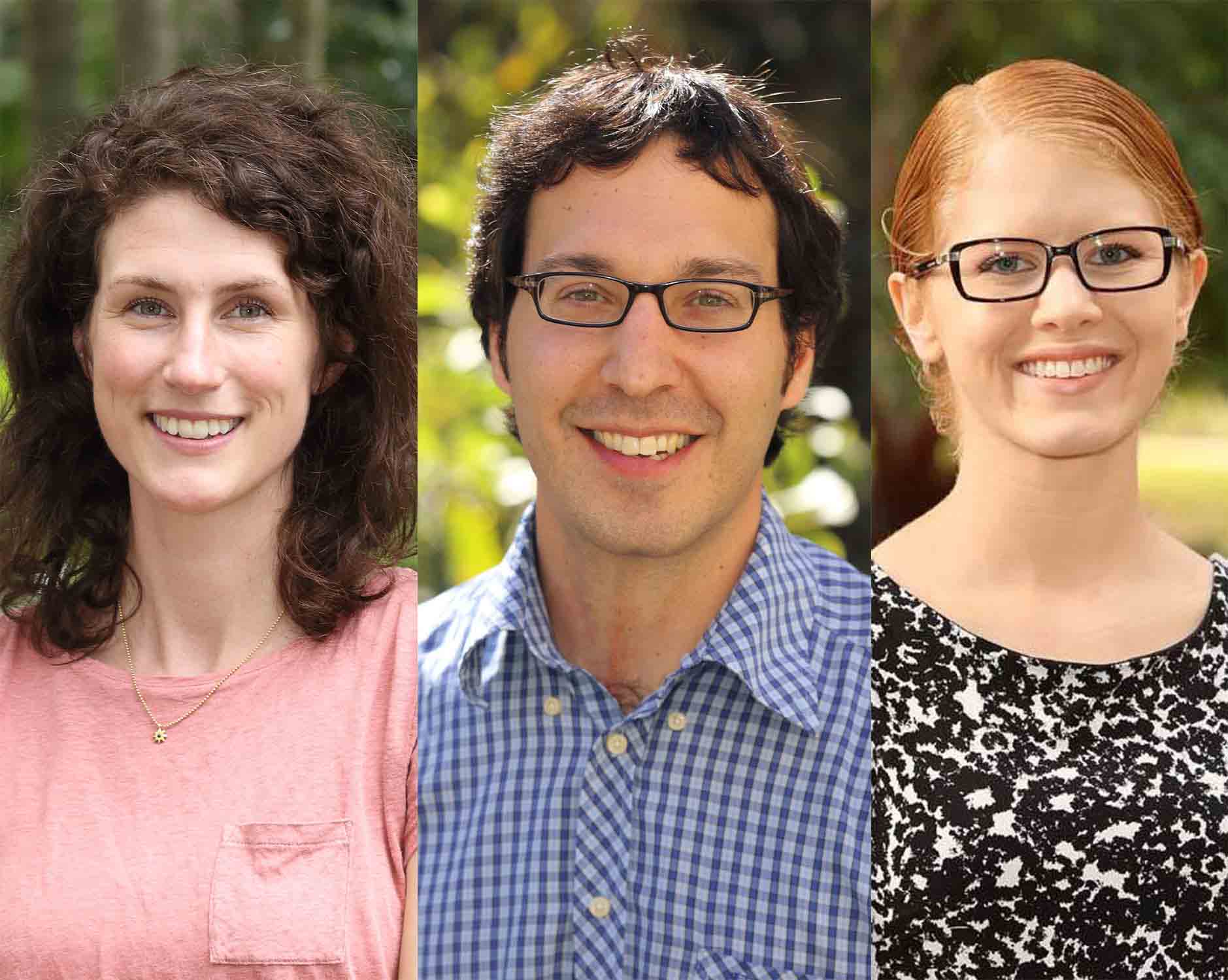

Dr Andrew Ventimiglia (post-doctoral research fellow)

Intellectual property rights are critically important for modern economies because the protections they grant across a number of disparate markets like media, software, and biotechnology, are central to nearly every global industry. As another intellectual property scholar Dan Hunter puts it, intellectual property is “like the air around us, invisible and unseen, but vital to our functioning.” At the same time, strong intellectual property rights should be balanced with other approaches that also foster innovation and creativity, for instance, the embrace of open-source and free software approaches in technology or the inclusion of robust fair use and fair dealing protections in copyright. A balanced approach to intellectual property is key to making the law work for a variety of industries and ensuring that it fosters economic gains while also guaranteeing the rights of users, consumer, and future creators and inventors.

Jocelyn Bosse (PhD student)

Intellectual property is a mechanism that can be leveraged for good, but also for undesirable purposes. In the interests of the rule of law, it is important to protect existing rights, but equally important to maintain a critical mindset about the future direction of the law. Where the current intellectual property regime does not perform beneficial functions, it may be necessary to move beyond the status quo and consider reform. In that vein, I address the conceptions of ownership under modern IP law, and how romantic ideas of authorship or inventorship can be inconsistent with the relationships between members of Aboriginal communities as traditional knowledge owners. Re-examination of the philosophy that underpins our intellectual property laws is a necessary, but often an overlooked, stage of the reform process.

Dr Susannah Chapman (research fellow)

For a very long time, people and states have used various tactics to influence the ways in which certain types of goods circulate and effect value as they move through society. It is important to explore these tactics so that we might always hold in question the value and history of particular visions of property, innovation, economy, and law. As a result, I think the approach to the study of intellectual property is not always about a commitment to protect or not protect intellectual property.

What role do intellectual property rights play in encouraging innovation and creativity?

Dr Andrew Ventimiglia

Intellectual property rights are designed – in the words of the United States Intellectual Property Clause – “To promote the progress of the Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.” In other words, intellectual property rights are given to authors and inventors in order to incentivise them to create and distribute the products of their genius to the public. Thus, these rights, even as they are given to particular creators and inventors, are ultimately designed to improve society and enrich the world. My own research on copyright in sacred and prophetic texts demonstrates that even in unexpected areas like that of religion, intellectual property rights have played a surprisingly important role. I have found that legal systems that guaranteed strong intellectual property rights encouraged innovation within new religious organisations who found copyright centrally important to their capacity to organise themselves in relation to their sacred texts and to network readers together as a unified community of believers.

Jocelyn Bosse

The intellectual property regime is often justified on the grounds that it is an incentive for innovative and creative activity. Such economic rationales are built upon relatively scarce empirical data, to the extent that they are based upon any evidence at all. Rather than focusing on the ideological discourse and conflicting explanations for intellectual property rights, I look at the innovative ways that Indigenous communities and their collaborators have used legal tools (like patents and contracts) to their own advantage. Aboriginal groups have entered into benefit-sharing agreements with scientific researchers to ensure that their interests in native biological resources and associated traditional knowledge are protected. I will examine how the unique circumstances of remote Australian food industries have spurred this creative thinking about intellectual property rights.

Dr Susannah Chapman

How intellectual property law comes to bear on different types of innovation varies across time, space, and the “protected” thing in question. For example, in the twentieth century United States, intellectual property rights actually played a relatively small role in the innovation of new, open-pollinated vegetable and apple varieties. For that same time, intellectual property rights seemed to play a slightly greater role in the markets for certain types of commodity crops—such as corn. In other cases, other types of non-legal protection, such as hybridity, factored into how or whether the breeders of new varieties sought legal protection over their innovations. On top of all that, for the twentieth century USA vegetable and apple markets, there was also a good deal of innovation that never intersected with either intellectual property rights (in this case patent or plant breeders’ rights) or other biological tactics that would affect how the plants in question moved across the economy.

Jocelyn Bosse will be discussing her research on intellectual property and food security at a seminar this evening hosted by the Australian Legal Philosophy Students’ Association. The seminar will briefly outline ‘a tale of two patents’ and compare the patentability of the Kakadu plum in Australia and the United States.

Find out more about the ARC Laureate Project Harnessing Intellectual Property to Build Food Security.