Solitary confinement in Queensland

A comprehensive report by UQ and the Prisoners Legal Service

Change is needed to comply with our human rights obligations and improve mental health for Queensland prisoners

Update: Litigation by the Prisoners Legal Service in October 2021, supported and informed by our research, resulted in a win for prisoners’ rights in the Queensland Supreme Court. View the judgement Owen-D'Arcy v Chief Executive, Queensland Corrective Services [2021] QSC 273 (22 October 2021).

Key points

- UN bodies have concluded that ‘solitary confinement should only be used in very exceptional cases, for as short a time as possible and only as a last resort’.

- In Queensland, it is the default position for managing difficult prisoners, some of whom have been held in isolation for more than a decade.

- It is not uncommon for prisoners in solitary confinement to develop symptoms of psychosis including delusions, hallucinations and paranoia.

- Conditions currently infringe upon a number of human rights including the right to be free from cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment.

- International best practice demonstrates alternative behaviour management strategies and specialist mental health units can remove the need for solitary confinement.

Download the full report (PDF, 2.4 MB)

About the report

For over eight years, Helen Blaber, Director, Prisoners' Legal Service, has provided legal services to prisoners in Queensland, many of whom have spent time in solitary confinement. In 2018, Helen invited Professor Tamara Walsh to undertake a joint PLS/UQ research project on legal responses to solitary confinement. This comprehensive report on solitary confinement and human rights is the result of this collaboration. Tamara and Helen worked closely with PLS staff, and a number of volunteer UQ Law undergraduate students, to complete this important research project.

There are a range of steps that can be immediately taken to prevent the negative health outcomes that solitary confinement creates for the most vulnerable members of the prison population. Read the recommendations.

What is solitary confinement?

Solitary confinement occurs when a prisoner is locked down in their cell for at least 22 hours a day with very limited or no association with other prisoners. There is often little or no access to natural light or fresh air, limited contact with staff, and reduced privileges such as televisions, visits and phone calls. Prisoners are typically locked in small cells, sealed with solid doors. Most contact with prison and health staff is perfunctory and may be wordless.

A prisoner lies in his cell in solitary confinement cell in the safety unit at Lotus Glen Correctional Centre, northern Queensland. Photo: © 2017 Daniel Soekov for Human Rights Watch

Solitary confinement and human rights

Judges around the world have recognised the harms that solitary confinement causes, and have held that placing someone in solitary confinement can constitute a breach of human rights including the right to humane treatment whilst in detention, and the right to be free from inhuman and degrading treatment. Judges have reduced the length of prisoners’ sentences in recognition of the harshness of the solitary confinement.

Australian coroners have found solitary confinement conditions to be ‘deplorable’ and external oversight to be ‘inadequate.’ They have noted the lack of access to appropriate health care and mental health care, as well as the association between isolation and the development of symptoms of psychosis.

Solitary confinement in Queensland legislation

Whilst the term ‘solitary confinement’ is generally not used in Australian legislation, many Australian prisoners are subjected to these conditions. In Australia, solitary confinement is referred to as segregation, separate confinement, isolation or non-association.

In Queensland, solitary confinement can occur under a safety order, under a maximum security order, or as a result of a breach of discipline. Since there is no limit to the number of consecutive safety orders or maximum security orders that can be imposed, prisoners can be held in solitary confinement for prolonged periods of time – for months, or even many years.

In Queensland, the Corrective Services Regulation 2017 (Qld) establishes some minimum requirements for prisoners subjected to solitary confinement. However, it is our understanding that some of these minimum requirements – such as the opportunity to exercise in the fresh air for at least two daylight hours a day – are not always provided. The Custodial Operations Practice Directives (COPD) provide guidance to corrective services officers on how prisoners should be managed. Yet some of these guidelines – such as those outlining the stages of reintegration for maximum security prisoners – are not reflective of actual practice.

The effects of solitary confinement

Prisoners in solitary confinement experience profound social and sensory isolation. It is well-established that placement in solitary confinement, even if only for a few days, can result in serious psychological harm that in some circumstances is permanent. It is not uncommon for prisoners in solitary confinement to develop symptoms of psychosis including delusions, hallucinations and paranoia. They may also engage in seriously disordered behaviour such as ‘bronzing’ (spreading faeces), and acts of self-harm.

The lived experience of prisoners revealed in this report may well ‘shock community conscience.’ Professionals who work with prisoners provide graphic descriptions of the conditions within solitary confinement, and the impacts of isolation on individuals.

‘I’ve seen people who I’ve worked with, when they’ve just gone into solitary, and I’ve gone back to see them six weeks later, and they have been unrecognisable.’

- Prisoners’ lawyers and advocates focus group participant

Observations in the report

The focus group of prisoner lawyers and advocates reported prisoners with serious mental health problems being placed in solitary confinement ‘for behaviour they can’t really control.’ They describe prisoners ‘doing things with their faeces’, routinely self-harming, and engaging in obsessive-compulsive behaviour as a ‘coping strategy.’

They note that prisoners in solitary confinement often become hypersensitive to noise, afraid of open spaces, and reluctant to be released from isolation.

They describe the profound loneliness and boredom experienced by prisoners, and the extreme sensory deprivation, including their complete removal from grass, air and colour.

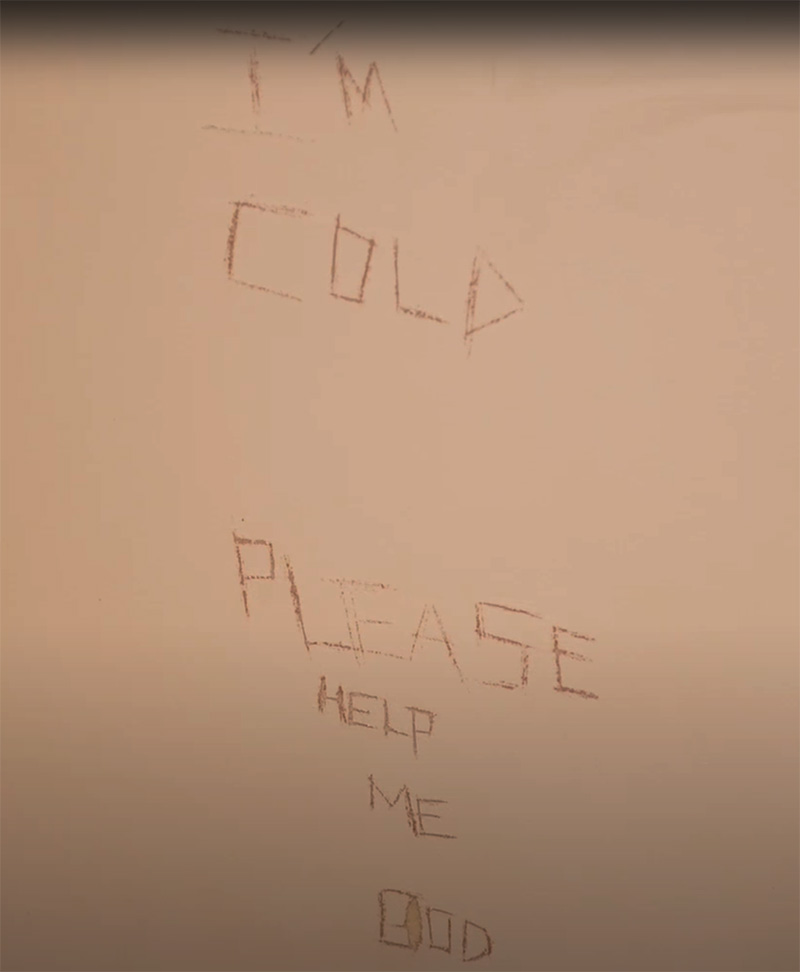

Isolation room wall: “I’m cold, please help me God,” at the Lotus Glen Correctional Centre, Queensland, Australia, July 31, 2017. © Human Rights Watch. Watch the full video.

Is solitary confinement torture?

United Nations bodies have concluded that ‘solitary confinement should only be used in very exceptional cases, for as short a time as possible and only as a last resort’ and that solitary confinement for more than 15 days at a time should be prohibited. Instead, in Queensland, it is the default position for managing difficult prisoners, some of whom have been held in isolation for more than a decade.

Considering the length of time that some Queensland prisoners have been in solitary confinement, the serious nature of their crimes, and the extent to which their mental health has deteriorated, releasing these prisoners from solitary confinement may seem impossible. However, this investigation shows that there are myriad alternatives to solitary confinement that can effectively address the safety concerns that tend to result in a person’s placement in solitary confinement in the first place.

A padded cell in Brisbane Women’s Correctional Centre, Queensland. Human Rights Watch documented at least three cases of female prisoners who were kept in windowless, perpetually lit, padded cells for several consecutive days, and in one case for over a month.

Photo: © 2017 Daniel Soekov for Human Rights Watch

Alternatives to solitary confinement

Focusing on prisoner mental health

International best practice demonstrates that alternative behaviour management strategies and the establishment of specialist mental health units can remove the need to place prisoners in solitary confinement. There are a range of methods adopted internationally to facilitate the effective reintegration of prisoners from prolonged solitary confinement, including through the use of step-down units and alternative behaviour management strategies.

Improving conditions in solitary confinement

Conditions in solitary confinement can also be substantially improved by increasing the amount of meaningful conversation that prisoners engage in, and the range of activities they can participate in.

Improvements to in-cell exercise and education programs, and in-cell work opportunities, could easily be implemented.

Technology can allow prisoners better access to music, audiobooks and audio programs, and can even be used to simulate outdoor experiences.

Amendments to the Corrective Services Act

The recent passing of the Human Rights Act 2019 (Qld), as well as Australia’s ratification of the Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture (OPCAT), will require Queensland Corrective Services to rethink its approach to solitary confinement.

The harshness of the conditions under which prisoners are currently held engages a number of human rights including the right to humane treatment when deprived of liberty, the right to be free from cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment, the right to life, liberty and security of person, and the right not to have one’s family life arbitrarily interfered with.

Whilst we acknowledge that a transition away from the use of solitary confinement will take time, substantial reforms are necessary to avoid future litigation and end a practice that causes significant harm to vulnerable individuals.

Recommendations

- That Queensland Corrective Services eliminate the use of solitary confinement, or segregation by any name.

- That the Corrective Services Act 2006 (Qld) be amended to:

a) require that prisoners receive a comprehensive mental health evaluation by an external mental health professional within 24 hours of a decision to separate them from the general population;

b) mandate that no prisoner be held in solitary confinement within 60 days of their release date;

c) require that correctional authorities apply to a court for authority to separate a prisoner from the general population for more than 48 hours.

- That Queensland Corrective Services immediately commence a process for undertaking meaningful engagement with relevant non-government organisations about solitary confinement reform.

Expert discussion video

Local and international experts examine the importance of this research and why solitary confinement should be abolished in Queensland prisons.

UQ Law research

Connect with our researchers

Collaborate with us to solve today's pressing challenges. Find out how we can work together.

Find a researcher by name

Find researchers by research area

Research themes & challenges

Potential HDR projects

Summer/Winter research scholarships

What's on

Research groups

Australian Centre for Private Law

Centre for Public, International and Comparative Law

Food Security and Intellectual Property

Indigenous People and the Law

Law and the Future of War

Law and Religion in the Asia-Pacific

Law, Science and Technology

Marine and Shipping Law Unit

UQ Solomon Islands Partnership